Il Museo di Storia naturale di Pavia fu fondato nella seconda metà del Settecento. Dal 2019, ha assunto il nome “Kosmos” e si trova in un’ala ristrutturata di Palazzo Botta Adorno la cui costruzione risale al 1693 ed è considerato la più bella dimora patrizia della città.Il museo vanta una tra le più antiche collezioni zoologiche al mondo. L’enorme numero di reperti non esposti nel museo è conservato in stanze rimaste per lungo tempo in abbandono: è a questi esemplari e agli spazi non accessibili al pubblico che ho dedicato la mia ricerca.I reperti sono in ottimo stato di conservazione grazie all’ARSENICO con cui furono preparati dai tassidermisti. Apparentemente obsoleti, costituiscono in realtà una fonte preziosa di informazioni genetiche. Sono animali immolati alla scienza. Le loro pelli avvolte su sagome di legno sono simulacri di esistenze passate per cui provo rispetto.

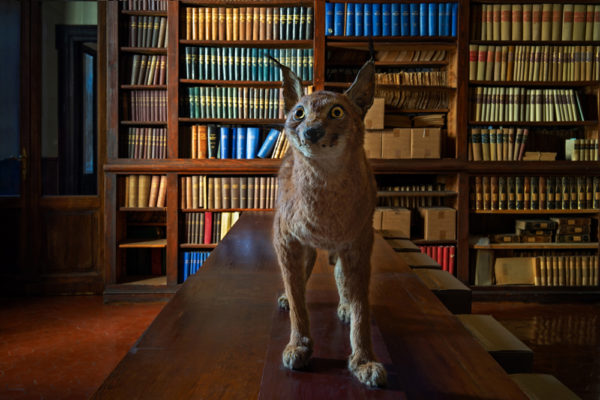

Gli ambienti sono tetri, silenziosi e irresistibilmente ammalianti. Ho fotografato dapprima gli esemplari dove si trovavano, coperti da teli di plastica. Poi ho cominciato a scoprirli, a spostarli, a ricollocarli negli ambienti. Per un breve momento della loro “esistenza”, sono diventati protagonisti perplessi, visitatori straniti, compagni incongrui della mia esplorazione. Infine sono tornati nel loro angolo di storia, come serbatoi di dati scientifici e ricettacoli di memorie di viaggi e scoperte.

L’arsenico uccide, ma allo stesso tempo è il mezzo con cui si conserva l’informazione vitale di queste creature. E grazie all’arsenico si salva il fantasma denso di significato di queste umili presenze-assenze che ci sopravvivranno.

The Natural History Museum of Pavia, Italy, was founded in the second half of the eighteenth century. Since 2019, it has taken on the name “Kosmos” and is located in a renovated wing of Palazzo Botta Adorno whose construction dates back to 1693 and is considered the most beautiful aristocratic mansion in the city.

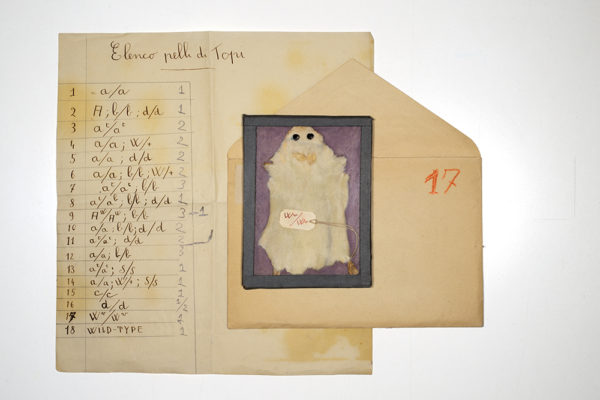

The institution boasts one of the oldest zoological collections in the world. The huge number of animals not exhibited in the museum are kept in rooms that have long been abandoned: it is to these specimens and to spaces not accessible to the public that I dedicated my research.

The specimens are in excellent condition thanks to the ARSENIC with which they were prepared by taxidermists. Seemingly obsolete, they are actually a valuable source of genetic information. They are animals sacrificed to science. Their skins wrapped on wooden shapes are simulacra of past existences for which I feel respect.

The rooms are gloomy, silent and irresistibly bewitching. I first photographed the specimens where they were, covered with cellophane sheets. Then I began to uncover them, to move them, to relocate them in the rooms. For a brief moment of their “existence”, they became perplexed protagonists, bewildered visitors, incongruous companions in my exploration. Finally, they returned to their corner of history, as reservoirs of scientific data and memories of travels and discoveries.

ARSENIC kills, but at the same time it is the means by which the vital information of these animals is preserved. And thanks to arsenic, the ghosts of these humble presences-absences that will survive us are saved.